Scrum: our three iterations

Contents

Yes, Scrum is now 100% buzzword. We learned about it in our university studies, we heard about it from corporate software engineers and consultants at the conferences, we see it in enterprise (see v1), we read about it in job postings, and some GSoC projects even impose Scrum to one-man "teams"!

However, it was not until this summer when I learned that it's actually an effective engineering technique. It revitalized the development of one of our projects (I'll later refer to it as "the Project").

Actually, the idea of adoption of Scrum was mostly inspired by one of our customers. A couple of our specialists worked in collaboration with another company on their product. The customer used Scrum, and held meetings in the room where our group sits. Our managers liked it, and we decided to try this framework.

So, we adopted Scrum for our project as well. When the idea emerged, I made a blog post referring to this idea as of a thought of a bored manager.

To make things less boring, I volunteered for a ScrumMaster role, and we spent three sprints (before we took a pause since the majority of our team went on vacation).

So, I've learned some lessons, and I want to share my thoughts on what Scrum is and how was it applied.

How I understand what Scrum is

First, what is Scrum. I won't repeat all definitions (you can find it on Wikipedia (frankly, quite a bad article) or here), just my perception of what it's really all about.

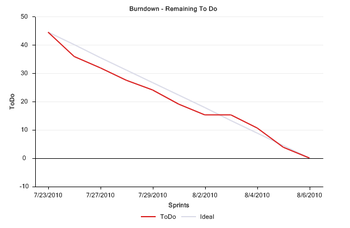

Our burndown chart

Here's our burndown chart of the 3rd iteration. It's created with use of VersionOne online agile project management tool (it's free for small teams with up to 10 developers!).

(To read the rest of the article, you should know base definitions of Scrum.)

Scrum values:

- permanent formalized evaluation of the work done

- early identification and discussion of problems

- frequently changing local goals (as an Agile tech)

- orientation to business values

The most important thing is the permanent evaluation. In the beginning of the post I mentioned that Scrum was used in a GSoC project. Of course it hardly was anything else but a disciplinary measure.

Early discussion of problems is also a valuable feature. During daily scrum developers are to speak about problems that prevent them from achieving their future goals. This is a required part of daily scrum, and it appears to be a valuable measure to keep things on time.

Frequent changing of local goals is a natural feature of any agile framework. Scrum's not an exception.

Orientation to business values is provided by separation of those who do the actual work (programmers) from those who make decision of how the product will look like (product owner). When we started doing Scrum, I noticed that nearly all items in my TODO list were replaced by the more valuable ones.

Scrum implementation

Scrum is not easy! Formal definitions say what should be done, but not how it should be done. I volunteered as a ScrumMaster, but only on the 3rd sprint I succeeded in leading a proper sprint planning. Scrum looks more like an interface, in the frame of which you can vary the actual implementation.

I can't explain every single nuance of our implementation. We have only established our way just moderately. And even if we would, it's a material for a 100-pages long book. Books is what you should pay attention to. The book that influenced our scrum the most is "Scrum from the Trenches", you can find the link at the "Acknowledgments" section below.

However, here's a couple of the most valuable notes.

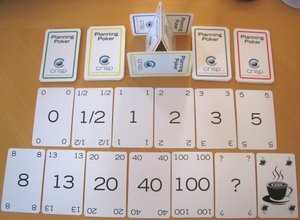

Planning poker

Here's an image of Planning Poker deck (taken from a site of a "Crisp" company, which sells them).We had printed similar cards and play them every sprint planning. The reasoning why they should be used is based on the fact that an expressed opinion actually affects what other people consider their own opinion. When people are forced to document their estimates independently, it usually leads to more productive discussions, into which the whole team is involved. You can read more about it at the site I already linked.

It appeared that planning poker is really useful during the sprint planning. Contrary to what you may think, it makes sprint plannings faster, as it brings in a formal pace of how the meeting should flow.

Some people suggest that sitting at the table and walking through the backlog is not effective. However, for our 4-man project, it's, in my opinion, the best way to hold it. As we play planning poker, I (as ScrumMaster) make notes about separation things to tasks, and after we select enough stories for the current iteration, we go through the notes, and form the actual tasks.

Downsides and lessons of Scrum

Responsibility

The first, quite a non-obvious consequence of adoption of Scrum, is that it makes developers even less responsible than they usually are :-). People start doing things not because they should, but because it was planned, because there's an action item, and you can't close it unless you complete it.

Motivation of developers

As I mentioned, Scrum teaches to talk about future problems, not about of the solved ones. However, this leads to underestimation of effort the developers made. If someone has successfully solved a tricky problem, and thus made the underestimated story completed on time, it's not possible to detect it in a usual workflow. This makes developers less motivated. To overcome this is a task of the managers, and Scrum doesn't help here.

Inflexibility

Scrum silently assumes that estimation of how much it takes to complete a task can be completed within minutes. To estimate all stories and tasks, (usually 10-20 stories) only 4-hour meeting is allocated.

It is probably true for most well-developed commercial projects. However, our Project was partly a research one, and it was unclear how much time an implementation of something that wasn't really done by anyone else before would take. For example, evaluation of one of the features in our project took a whole week!

We solved this problem by

- making sprints shorter (2 weeks long)

- introducing "research stories"

When the "product owner" required to implement such a story, which needed additional research for its estimation, we first asked him to add "research story". An outcome of a "research story" is not an implementation of the feature, but rather a report that contained evaluation of several ways to implement the feature. Of course, several approaches to the problem have to be prototyped, but the quality of such prototypes shouldn't make the developers spend too much time on them.

The report is analyzed upon a completion of such a story, and one way to implement the feature is selected by the product owner. Then implementing of this approach is added to backlog, and is to be addressed in the nearest sprint (or the owner may decide that the feature is not worth it).

Of course, to increase the pace, we made the sprints short (2 weeks is commonly understood as a minimum value of sprint length).

Lack of code quality criteria

Tasks and stories are required to speak business terms. However, what if there's a need to refactor code, to set up a new logging system, or to fix the architecture with no obvious visible outcome?Focus factor (also known as "fuckup factor") is a multiplier for the available man-hours of the team. If your focus factor is "70%", it means that the team can only promise to deliver the amount of stories that takes 70% of its total man-hours. The rest of the working hours is to be spent on doing the "backend" work, which doesn't reflect concrete user stories.

70% is a "recommended" value for the focus factor, but its actual value may vary for different teams and projects. For our team it's 80%, because the Project doesn't have many users, so few bugs are filed.

The standard way is to decrease the "focus factor", and let developers decide how to spend the available time. If there's a great need for refactoring, there's a limited amount of time to be spent on it.

Prespecifying focus factor also makes the team choose wisely what to refactor, as they know they can't spend all the time on that.

Who fixes the bugs?

Some bugs are planned, but some are not! Some bugs get reported by critical customers, but--surprise!--all your working hours are already allocated between different stories. Who fixes the bugs then?

The obvious solution would be to allocate some more time on fixing critical bugs into the "focus factor" mentioned above. Non-critical bugs with lower priority can be made stories for the next sprint.

Scrum requires robots

Integrity and uniformity of the team is required for Scrum to work well. Days off are local catastrophes, and a sudden illness of a developer is a great catastrophe, which may result in a failed sprint (we're experiencing this right now).

It's obvious that Scrum would work for robots better, than for humans. However, if such a problem occurs, it requires really non-formalized, "human" thinking to resolve it.

Acknowledgments

The most fruitful source of information on how to do Scrum was "Scrum from the Trenches" (free pdf version). Shyness aside, having read Wikipedia definitions and this book, I became not the worst ScrumMaster in the world.

And, of course, experience matters. Our managers, Vladimir Rubanov and Alexey Khoroshilov, helped the team a lot to facilitate Scrum efficiently.

Conclusion

Another interesting thing I noticed, is that working without any formalized process is more boring than with it. Some time ago I assumed that it's like having sex in a new position, and after I tried that (Scrum, not sex), I realized that it was a very exact guess.

Though not ideal, Scrum appeared to be a very effective framework. It comprises both agile values and what commercial development wants, thus being the most popular agile framework. Its bureaucratic procedures (maintaining a backlog, doing scrums, drawing burndowns) are totally worth the net positive effect on development speed and quality.