Traffic IV: How to Save 10 Minutes on your Commute, or the Mystery of the 101-92 Interchange

Contents

Driving on a highway is like picking stocks. There are multiple lanes, and as we established earlier, one of them is just faster than the others. Drivers take notice; they move into the lane just like the stock market players “move into” the stock of a promising company, buying its shares.

Then, the same thing happens as in the stock market: as more cars occupy the lane, it becomes more congested, and it slows down. The lane is no longer “profitable”, and other lanes start to outpace it. Recall the passive investment wisdom: no matter how hard you try, you will still move with the average speed of the flow (or, likely, worse). Unless you possess uncanny talent, or can see the future, or have insider knowledge, you have no advantage. On a freeway, talent won’t help, and as for seeing the future: you barely see behind that truck just ahead.

But I do have some insider knowledge for you. How come some commuters drone it out for 15 minutes in bumper-to-bumper traffic and those few “in the know” zoom past them and beat them to the next exit? Read on–or skip to the solution.

Series on Car Traffic modeling

Inspired by my almost daily commute on California Highway 101, I explored the achievements of traffic theory and found answers to the most pressing mysteries of my commute.

Enter the intersection of Highway 101 and Highway 92

Or, rather, enter the gigantic southbound traffic jam that “happens” there every single weekday, from 6.30am to 10am. The jam is so reliable that some atomic clocks use it as a backup time sync mechanism.

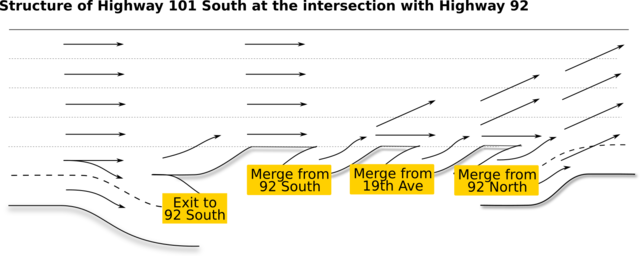

What happens there is simple. Three (!!!) different streams of traffic merge into this already clogged 4-lane highway: local 19th Ave, eastbound Highway 92, and westbound Highway 92, all full of techies anxious to make it to their 10am standup meeting. (Note that I might have mixed up the order of the on-ramps, but it’s not important for our purposes.)

The small outlet onto 92 doesn’t help as few people travel in that direction during peak hours. Or… does it?

If you’ve been a diligent student of traffic laws in the last several posts, you can see what’s happening here. The interchange is an interplay between four traffic situations:

- right exit reducing the amount of traffic in the right lanes,

- a slowdown at a merge that is causing the blockage in the right lanes.

- “friction” that “carries over” the slowdown from the right lanes to the left lanes.

- faster left lane getting backed up before the blockage.

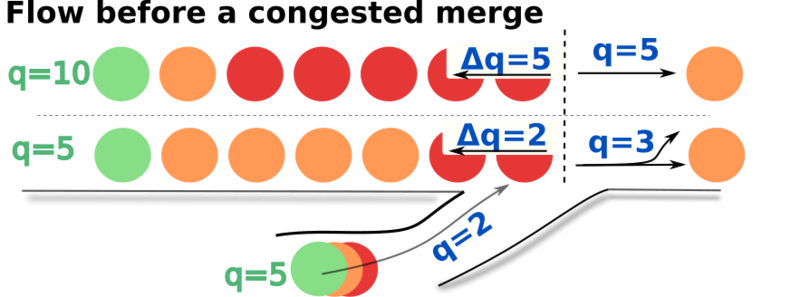

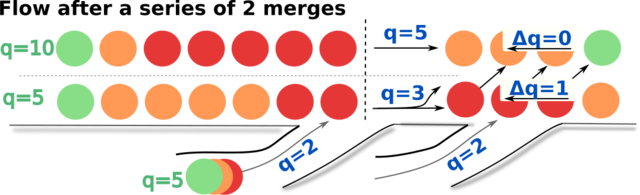

We know from Traffic II that if there’s a blockage affecting all lanes, then the left (the faster) lane will be backed up more (this is pattern (4)):

(Here, the green circles mean “free flow”, the yellow “mild congestion, and the red “severe congestion”.)

What causes the blockage in the left lanes? It’s the friction from the blockage in the right lanes. What causes that? The three freaking merges that dump San Mateo and East Bay commuters onto 101.

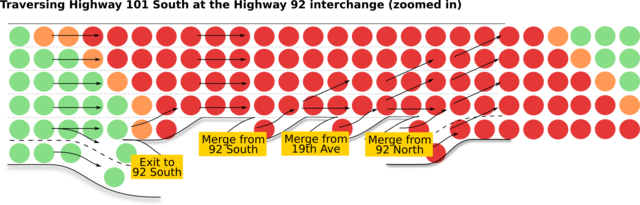

So the traffic jam unfolds the same way every day: patterns (1) and (2) make the right lanes more congested, (3) carries over the slowdown from the right lanes to the left, and (4) causes the slowdown in the right lanes way way before the interchange. Here’s what the traffic looks like there:

The optimal strategy

So how do you beat the rat race? You got it: drive in the rightmost lane, and then merge left five times.

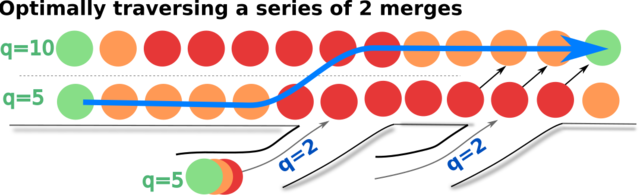

Indeed, in a simple two-lane case, the best way to traverse the blockage at the merge is to merge right just before the merge:

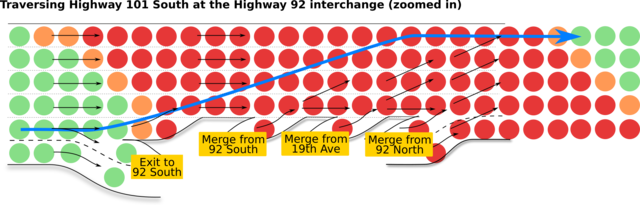

So when we apply this rule to the overall situation at the interchange, this would be the optimal strategy:

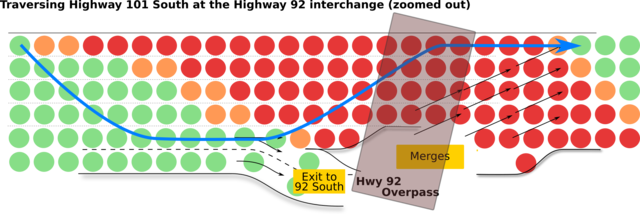

This doesn’t seem like much, but that’s because this model is very compressed. If we zoom out, the traffic would instead look like this:

It’s not easy and it is a bit stressful. Most prefer to just stay in the lane and relax, but if you want to get ahead in life, you gotta put some work in. Merging is tight: commuters do not appreciate the “freeloaders”, but it’s easier than it seems, just like the prior research shows.

A common mistake is to merge too early. Yes, I know you want to be conservative; yes, I know it’s hard to patiently watch that traffic slows down ahead of you; you want to react, you want to merge left, away from the impeding congestion… This is a mistake. If you’re in the right lane on 101, merge under the bridge, not before! Exercise patience. You’re the traffic tiger next to a flock of antelopes. Wait.

Another trick, employed by some shuttle bus drivers is to exit the freeway and immediately enter it. However, this involves a traffic light, and in my experience it’s not as fast as five merges (but if you’re driving a bus, merging is indeed more complicated).

Appendix

If you’re curious, I’ve filmed two videos of this interection.

Approach from Highway 101. Notice how three traffic lanes are merging into 101, and how motorists are merging leftwards. Before the overpass, the left lanes are more congested, and the traffic in the right lanes moves faster. However, as the camera approaches the overpass, left lanes pick up speed while the right lanes come to a standstil.

Approach from Highway 92. This time, we are merging into the right lanes that stall. Note how somewhat small amount of traffic coming off of Hwy 92 comes to a disproportinally slow merge at Hwy 101. You can also notice, at the time of merge that the left lanes are moving way faster than the merging lanes.

(Also some dude confused the shoulder with an extra lane… Oh if only!)

***

This concludes the traffic series. I originally wanted to write some simulations, but I realized there’s already a large body of work.

If you’re reading from outside of the US, you might be puzzled by what happens. In California, unlike on the East Coast or in Europe, drivers do not have a culture of staying in the right lane and using left lanes to pass only. Everyone basically drives wherever they want.